US debt - stuck in a vicious cycle

In recent weeks, investors have been focused on the imminent threat of a US default which would be extremely unnerving for global markets. This has overshadowed some of the real challenges facing the economy and consumer from the US’s swelling debt balance. As we await the full details of the agreement between the Republicans and Democrats, it is worth considering the debt derived challenges that will likely play out going forward.

US debt currently sits at $31.4tr (the current debt ceiling), or 119% of GDP, and the new bill, which will be the 79th time the debt limit has been increased since 1960, is set to leave debt levels uncapped until 2025. Since 2008, the US has added $22 trillion of debt and $8tr has been added since 2020 – this is a staggering amount, and it is important to consider the wider implications of this burden for the US economy.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service

The low interest rate environment since 2008 has made servicing this ballooning debt balance possible without limiting government spending. However, as we enter what may be a ‘higher for longer’ rates environment, the government’s significantly higher and rapidly increasing interest bill is likely to require trade-offs elsewhere.

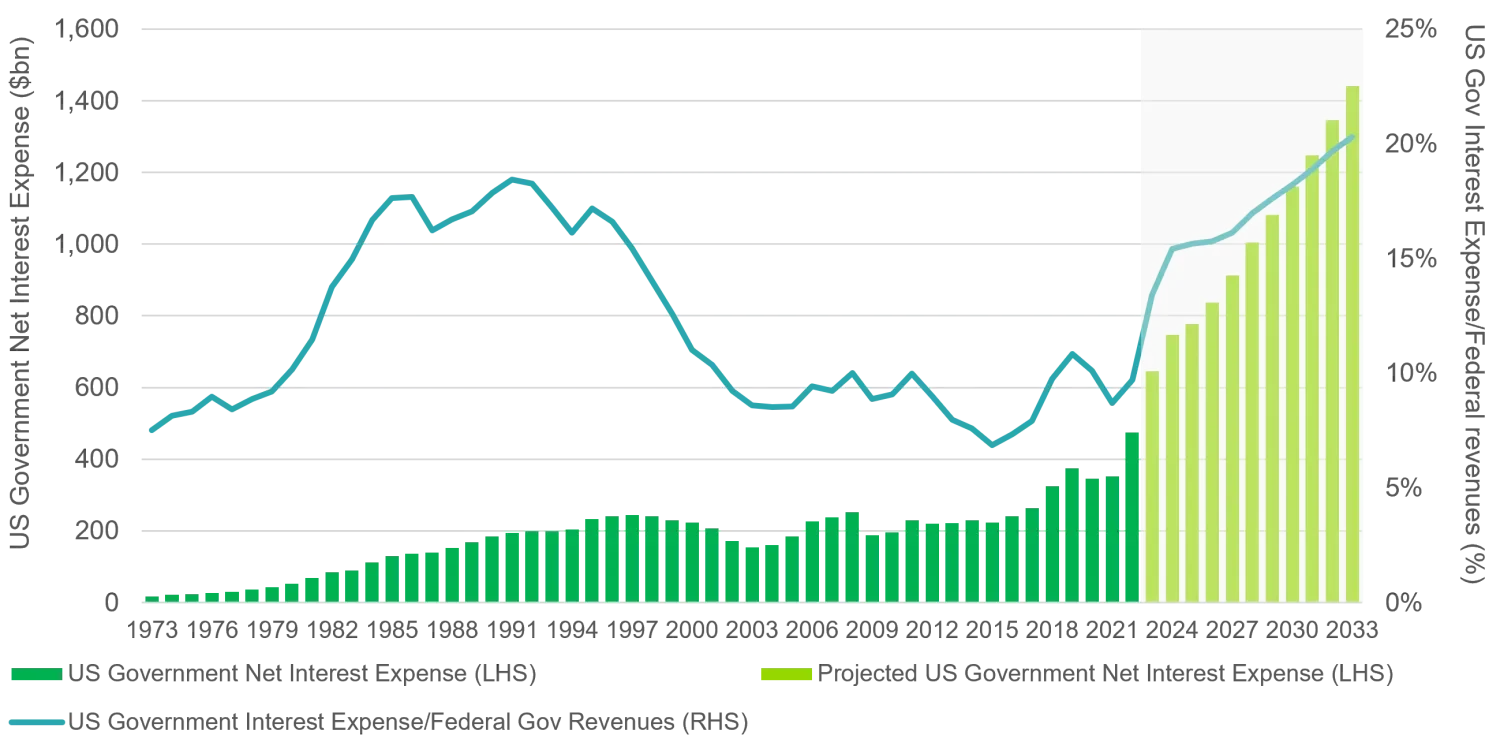

As the US continues to refinance debt at higher rates, the annual interest burden will continue to increase. To put this in perspective, if we assume today’s debt balance of $31.4tr was refinanced at current market levels, approximately 4% for example, the annual interest bill increases to $1.3tr, almost triple the 2022 level and would represent 27% of federal revenues. However, this is an unrealistic assumption as governments have a long ladder of maturities at a wide range of interest rates. A more accurate, but still alarming, picture is painted by projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which assume the 10-year Treasury yield will remain around 3.8% through 2033.

Source: CBO's February 2023 report The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2023 to 2033.

The CBO forecast interest costs to grow 35% this year to $645bn, up from $475bn in 2022 and $352bn in 2021, and to reach $1.4tr in 2033. To put this in context, interest costs as a percentage of federal revenues (tax receipts) are forecast to reach over 20% in 2033, more than double the 10% level recorded in 2022. Currently, interest costs represent 2% of GDP but this number is forecast to increases to 3.6% in 2033 and even set to surpass spending on Medicare and Social Security before 2050.

The structural mismatch between government revenues and spending (2022 budget deficit was $1.4tr) is set to widen further, fuelled by rising healthcare costs, an ageing population, and the increasing interest payments outlined above. The reality of this is an increasing portion of government capital is being used for unproductive means (debt servicing) rather than growth generating fiscal activities and we think this represents a real challenge for policymakers going forward.

The Federal Reserve is not helping the situation either. Central banks are no longer suppressing yields, and while interest rates may have reached or be very close to their terminal level, the Fed will continue to tighten financial conditions through its Quantitative Tightening (QT) program. QT involves actively selling Treasury securities that the Fed has accumulated since 2009. This action will continue to put upward pressure on government rates, remove liquidity from the market, and further drain productive capital from the economy. The market impact so far appears to have been limited, but this is expected to be a long and drawn-out process and that creates a challenging technical environment for government rates. Higher rates will lead to higher budget deficits, which will lead to higher debt balances – a vicious cycle that is difficult to break.

As Debt-to-GDP is set to increase, tackling the debt component seems like an impossible task and the best route out, which is traditionally favoured by policymakers, is to grow the economy. However, doing so is very difficult when constrained by an incredibly high interest burden and cutting taxes is not seen as a viable option to stimulate growth. As an example, recent debt ceiling negotiations prohibit a further extension of the pause in student loan payments and interest which were suspended at the start of the pandemic (March 2020). In essence this is equivalent to increasing taxes on a significant number of consumers and reflects the dilemma facing the government.

For over 43 million Americans, student loan payments are set to restart as soon as September. This represents 13% of the population, or 21% of the working age population, where the average monthly payment is set to be $393 with a median monthly payment of $222 according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The reality of this will be a huge drain on disposable incomes that has gone somewhat under the radar and leaves 43 million Americans, having already ran down pandemic accumulated savings, adjusting downwards their monthly spending and is undoubtedly a headwind for GDP. For risk assets, weaker growth traditionally translates into a deterioration in credit fundamentals, default rates increasing and investors shying away from higher beta investments. Credit spreads typically also widen and as such investors must be selective - not every business will be a winner like in an up market which we think highlights the importance of active management at this stage of the economic cycle in particular.

The U.S. debt negotiations look to be nearing an end, but regardless of the finer details, we know that debt levels will continue to rise, interest costs will increase, and budget deficits will widen. This is because there is no ability or appetite for deep spending cuts or tax increases, as both parties are focused on winning over voters ahead of the 2024 election. It is important to remember that the U.S. is not a business, and it is not subject to the same financial constraints such as leverage and interest coverage. The U.S. is the largest economy in the world and the dollar is the global reserve currency, which means that Treasuries are still the go-to asset for investors seeking safety. As a result, even with rising debt levels, market participants will always have a use for U.S. Treasuries. However, as interest payments take up a larger proportion of the government’s budget, pressure will naturally be felt in areas of government spending and investment.

Ultimately this widespread tightening reaching every area of the economy is the necessary evil needed to fight inflation. As capital is drawn away from productive activities and into unproductive ones economic activity will decline and may trigger the recession many are expecting. In the end, all parties are incentivised by low rates but for the time being there are tough hurdles for the economy to overcome.