Diverging dynamics in savings ratios

Savings ratios have been key in supporting growth post Covid. This is particularly important in developed economies where consumption represents close to 70% of GDP on average. As governments around the world provided support in various manners during the pandemic, savings ratios increased to levels that were twice as large as the previous all-time highs in some countries. This was a result of income being supported by government transfers, while spending plummeted both as a result of uncertainty and restrictions. As consumers adjusted and restrictions were gradually lifted consumption resumed; more visibly first in goods and then in services. Savings ratios also started normalising as consumers spent a larger percentage of their monthly income on goods and services.

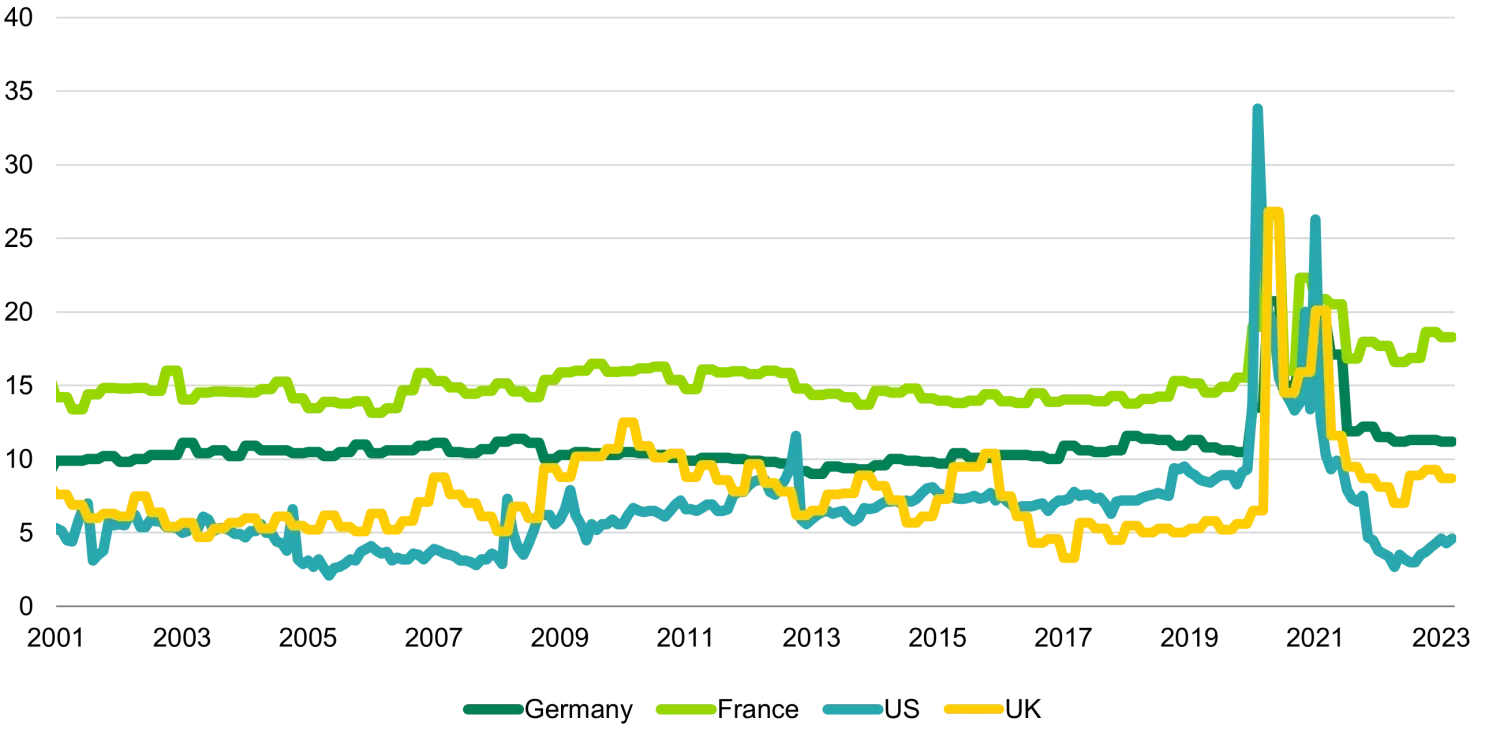

It is interesting to note, however, that trends in savings ratios have diverged somewhat between the US, Europe and the UK from their respective peaks. The graph below shows savings as a % of disposable income; it is important to note that this is based on monthly data. This is to say that US consumers are still saving circa 5% of their disposable income every month on average even if the % has come down from the peak. The most relevant comparison in our opinion is each series’ current value with their own history. This is because there might be methodological differences in the way different statistics offices calculate disposable income thereby making direct comparisons less meaningful. For instance some might include pension payments or benefits while others might not. Consequently we would argue against concluding that French consumers are the most conservative in the sample below, for example.

What is clearer to us is that US consumers have gone below their pre pandemic spending vis-a-vis savings patterns while German, French and UK consumers have not. Given that consumption stands for the lion’s share of GDP in these economies, the impact on growth is quite significant. This is one of the factors that explains why growth in the US has been stronger than in Europe in the last few quarters. The big question then is: is a lower savings ratio desirable in order to achieve a better growth outcome? Although the answer might be more obvious for equity investors, we think this is indeed a tricky question for fixed income investors. A higher savings ratio than in prior periods means that the cushion is larger in case consumers run into trouble. Trouble could mean a mild recession, a stagnating economy, higher mortgage payments as floating rates reset or an increase in unemployment just to name a few. Defaults and non-performing loan (NPL) formation on banks’ balance sheets certainly have less room to increase in a scenario where consumers save more. To be clear, we are not saying that US consumers are in bad shape. We are simply stating that lower growth in exchange for larger protection buffers is not a bad thing for credit investors.

In conclusion, we like the fact that consumers save more than pre pandemic. As fixed income investors we do not share in all of the upside that more growth brings about and, as has been abundantly clear, too much growth might mean government bond curves sell off resulting in temporary capital losses for bond investors. In the case growth turns out to be worse than our base case of a mild recession we would expect some of these savings to be deployed and consumption to be stronger than otherwise would normally be the case, albeit still weak. This should in turn help to keep defaults and NPLs under control.

Savings ratios - % of disposable income

Source: Bloomberg, 2023