Do green bonds deliver for fixed income investors?

As with many things ESG related, interest in, and issuance of, green bonds is growing rapidly. ‘Green bonds’ are debt securities issued with the purpose of raising capital to be deployed in infrastructure and projects aimed at improving environmental issues. We can all agree that is a positive aim and those of you who have read our previous ESG whitepapers, ‘ESG at TwentyFour’1 and ESG and ABS at TwentyFour’2will know that we definitely like to reward demonstrable positive momentum (transition) in our ESG Integration model. Positive actual outcomes are more important than just a positive aim though.

So far almost all of these bonds have been conventional investment grade debt, including those issued by sovereigns. These complementary factors led us in the Outcome Driven team to ask the question, ‘should we launch a green bond fund’? Central to that question is, ‘Do Green Bonds Work for Investors’?

Established clients of our firm will know that before launching any new fund the first question we ask ourselves is, ‘does it make long term economic sense for our investors?’ In addition, when thinking about sustainability we also have to ask if investors’ expectations can be fulfilled. This question also formed the basis of another whitepaper, ‘Sustainable credit: A free lunch?’3 The following whitepaper is a summary of our research into these questions.

What precisely are green bonds?

Green bonds are debt instruments where proceeds will be used exclusively to fund or refinance ‘green’ projects. That is the easy part, however. There is not a definitive list of what constitutes a green project but examples include: renewable energy, clean transport, pollution prevention and control, energy efficiency, green buildings and sustainable water management. Ultimately green projects should help improve the environment. In addition to the green bond market, there are smaller segments such as that of blue bonds and social bonds. The difference between the bonds are determined by the use of the proceeds – while green bonds facilitate environmental improvement, blue bonds finance ocean-based projects and social bonds raise capital for new or existing projects intended to have a positive social impact. Green bonds are by far the larger of these markets.

The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) has issued a set of Green Bond Principles, which while entirely voluntary provide a useful guide to the general ethos.

- Use of Proceeds – provide a clear environmental benefit

- Process for Project Evaluation and Selection – communicate the environmental objectives, the process for determining eligible projects, and processes for managing sustainability risks associated with the projects

- Management of Proceeds – net proceeds to be held separately and tracked so they are only used for green projects

- Reporting – transparency about projects, their expected and actual impact

Despite this guidance it is important to note that currently there exists no uniform, rigid standard of what constitutes a green bond. Ultimately issuers self-certify their debt as green, which can lead to ambiguity and disagreement. For example, the Climate Bonds Initiative refused to list a bond issued by Repsol due to concerns on the use of proceeds, but the bond was still included in green bond indexes. The European Union has proposed establishing an EU Green Bond Standard, but this has been in the consultative stages for some time. Ultimately there is no guarantee the global market will take up whatever definitions the EU or anyone else settles on. This leaves the sector at particular risk of “greenwashing” – where companies inflate their sustainable credentials. We will go into more detail later in this paper on the issues surrounding Repsol’s green bonds.

What expectation can green bonds fulfil?

How then can green bonds have a positive impact on the planet? Investors believe their money is solely being used as a force for environmental improvement and by lowering the cost of capital more green projects are incentivised.

At TwentyFour we place a high degree of importance on ‘momentum’ when making our ESG considerations, which means that we like to see and assess a company’s plan and demonstrable execution towards improving its ESG credentials. We feel the jury is still out on how effectively green bonds encourage momentum. While on the face of it their existence may create a two-tier system of capital that encourages companies to choose green projects over non-green ones, it is equally possible that simply ring-fencing the green parts of a company and financing them separately will ultimately create no change in the proportion of actual green projects. Perhaps if green bonds grow to be a more significant proportion of the fixed income universe we will see more evidence of this one way or the other – only time will tell.

Impact is only one of the reasons for allowing ESG factors to influence investing. There is an increasing body of research suggesting that investment strategies focusing on broader ESG goals can be better long term investments compared with their non-ESG counterparts. Partially this is because as more investors focus on ESG, demand for companies which score highly in their ESG assessments will naturally rise, but also because considering ESG factors can help identify additional risks and screen out poorly run firms. Green bonds must see their proceeds used for environmentally sound projects – but there is no requirement that the company’s governance achieves a higher standard, nor that social factors such as community relations or the safety and wellbeing of the workforce are above some threshold level.

Even a bond which unequivocally meets the environmental standards we would expect from a green bond could easily be issued by a company with serious issues in the S and G departments. That does not mean that we think green bonds do not have a place in a socially responsible portfolio, but it does mean we believe a ‘green stamp tick box’ itself is not enough. A thorough analysis of the company from an ESG perspective will be needed in addition. When we examined the universe of green bonds, described below, we noted that many had an associated ESG score which would make them ineligible for our own sustainable fund. So a passive investment into green bonds may expose an investor to avoidable risks and leave them invested in companies whose overall ESG profile is less than desirable.

This section began with the question, ‘What precisely are green bonds?’, and in truth the market is currently nowhere near precise, both in terms of definition and potentially meeting investors’ expectations.

The market for green bonds

It is worth considering whether a different investor base conveys any useful benefits to investing in green bonds. We wondered if a higher proportion of green funds were less active, with green bonds more tightly-held and thus more likely to outperform non-green funds during a market sell-off. Anecdotally, the first European non-financial issuer after the depths of the COVID-19 panic was Engie, with a green bond issued on March 20, 2020. This further fuelled the theory that institutional buy-and-maintain green bond funds had cash to invest in the sector having been less likely to suffer or worry about redemptions over that period, thus implying that green bonds would have been under less selling pressure. However, an extensive study undertaken by Barclays Capital, ESG Research: Green is but a colour, found that while green bond indexes have held up better during sell-offs they concluded this is simply a function of their greater proportion of higher rated bonds and lower beta sectors than the market as a whole. When controlling for this and examining how green bonds behaved relative to equivalent non-green bonds across multiple markets, there was no evidence of green bonds helping to offer any additional protection in sell-offs.

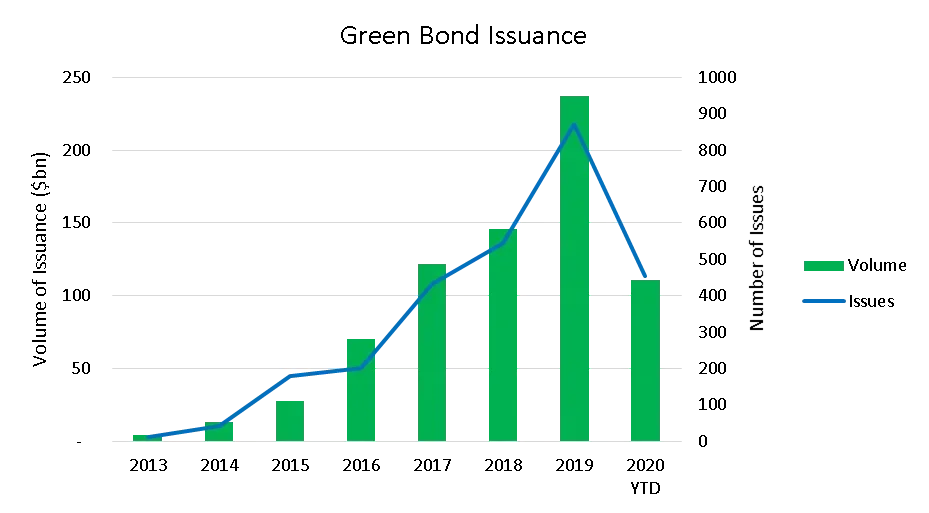

While interest in, and allocation to, green bonds by investors has grown substantially in recent years, so has issuance. Green bonds have been around since 2007 when the European Investment Bank first issued one, but it is in the last seven years that the market has seen dramatic growth. In 2019 we saw $237bn of issuance, a 62% increase on 2018’s $146bn, from a mixture of sovereigns, financials and corporates. However, despite adding over $100bn to the green bond corporate sector, which stands at roughly $244bn today, we still view lack of diversity as an obstacle; there are only 194 unique corporate green bond issuers.

Chart 1 – Green Bond Issuance & Volume:

Source: Bloomberg, as at July 7, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

Green bond fund sizes are growing

Dedicated green bond funds make up a small fraction of the fixed income universe, but they are growing rapidly. In 2017 there were no green bond funds with assets over $500m and only 11 holding more than $100m – now there are four with more than $1bn in AUM and 18 over $100m. Of the $11bn presently held in dedicated green bond funds, $4.2bn was gathered in the last year. The expectation is demand will continue growing as large numbers of investors become more focused on sustainability concerns. As more corporate issuers come to the market diversification should become less of a concern, possibly paving the way for more funds.

Given this context, we don’t think it would be a challenge for TwentyFour to launch its own green bond fund. We have argued however that the ‘green bond’ label/sector requires some considerable analysis to make sure investors’ expectations can be truly met, which is not necessarily a show-stopper as we are active managers who can do the work required.

So, what about the return prospects for an investor in a green bond fund?

Factors helping to drive green bond risk and return profile

Using ICE/BofA data from the inception of their “Green Bond” Index at the end of 2010, it can be seen from Chart 2 below that the universe grew slowly at first, starting with just seven bonds and a market value of less than $2bn, up to today with more than 500 bonds and nearly $500bn capitalisation.

Chart 2 – Market Value of Green Bonds vs Other Fixed Income:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

As a proportion of global IG credit, clearly green bonds remain small at 3.67%, but the growth profile has certainly picked up in recent years. As the above chart also shows, however, the bulk of issuance in the last two years has come from sovereigns (part of the broad market indices) with credit growth still positive but to a lesser extent, and the composition of sovereign-linked issuance within the green space has also ramped up dramatically in recent years.

The index is dominated by two currencies, EUR and USD, which together account for 90% of the issuance. However, there is a long tail of currencies including CAD, SEK and AUD with respective larger weightings than might be seen from a broader IG credit index, as shown below in Chart 3.

Chart 3 – Green Bond Index Composition by Currency:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020.

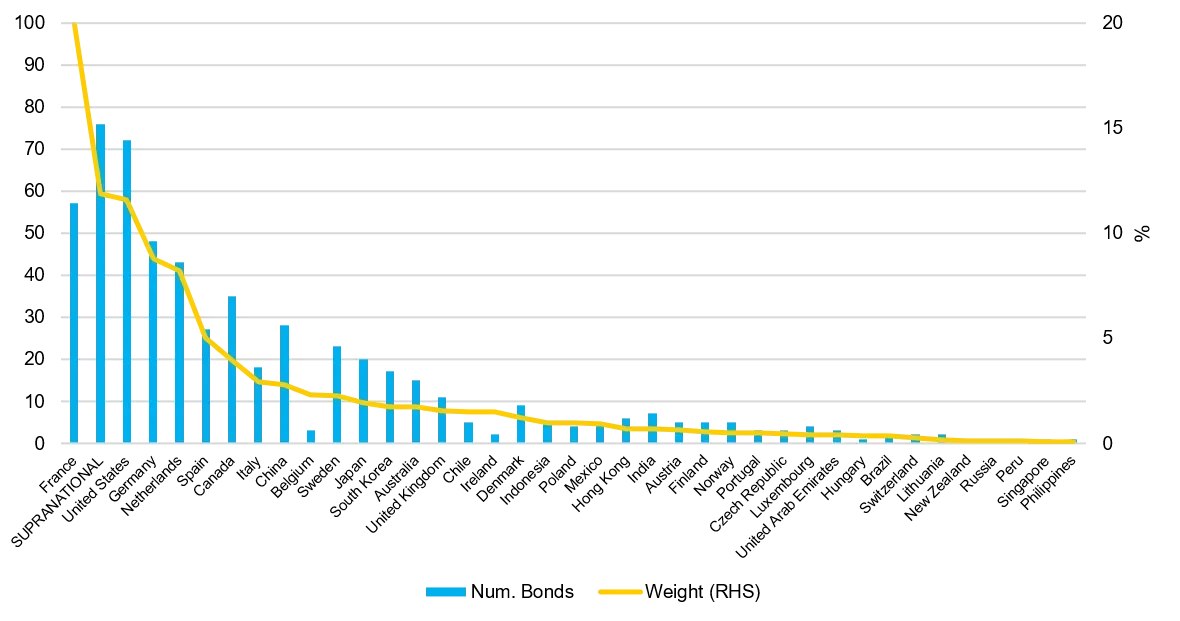

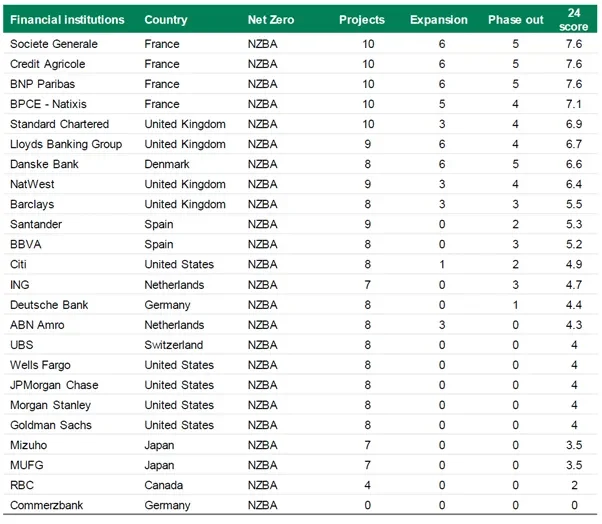

The currency profile however actually masks the large dispersion of issuing countries within the green bond landscape, and when splitting out the index by country, France in particular stands out, given it accounts for 20% of green bond issuance, as shown below.

Chart 4 – Green Bond Index Composition by Country:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020.

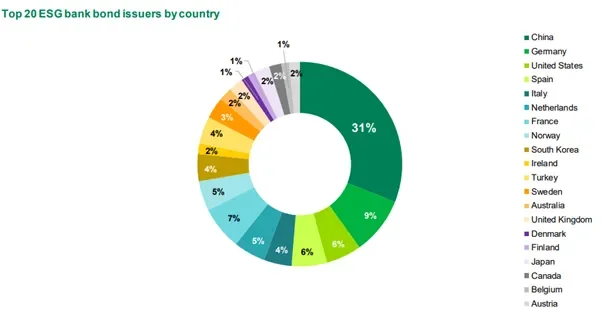

Perhaps not surprisingly, supranational issuers are a significant part of the index, given their remit is often to invest in large infrastructure projects advancing green initiatives within countries. On the flipside, some investors may be surprised to see China being a top ten issuer within the index, and ahead of green issue leadership countries such as the Nordics, and even G7 countries such as Japan and the UK.

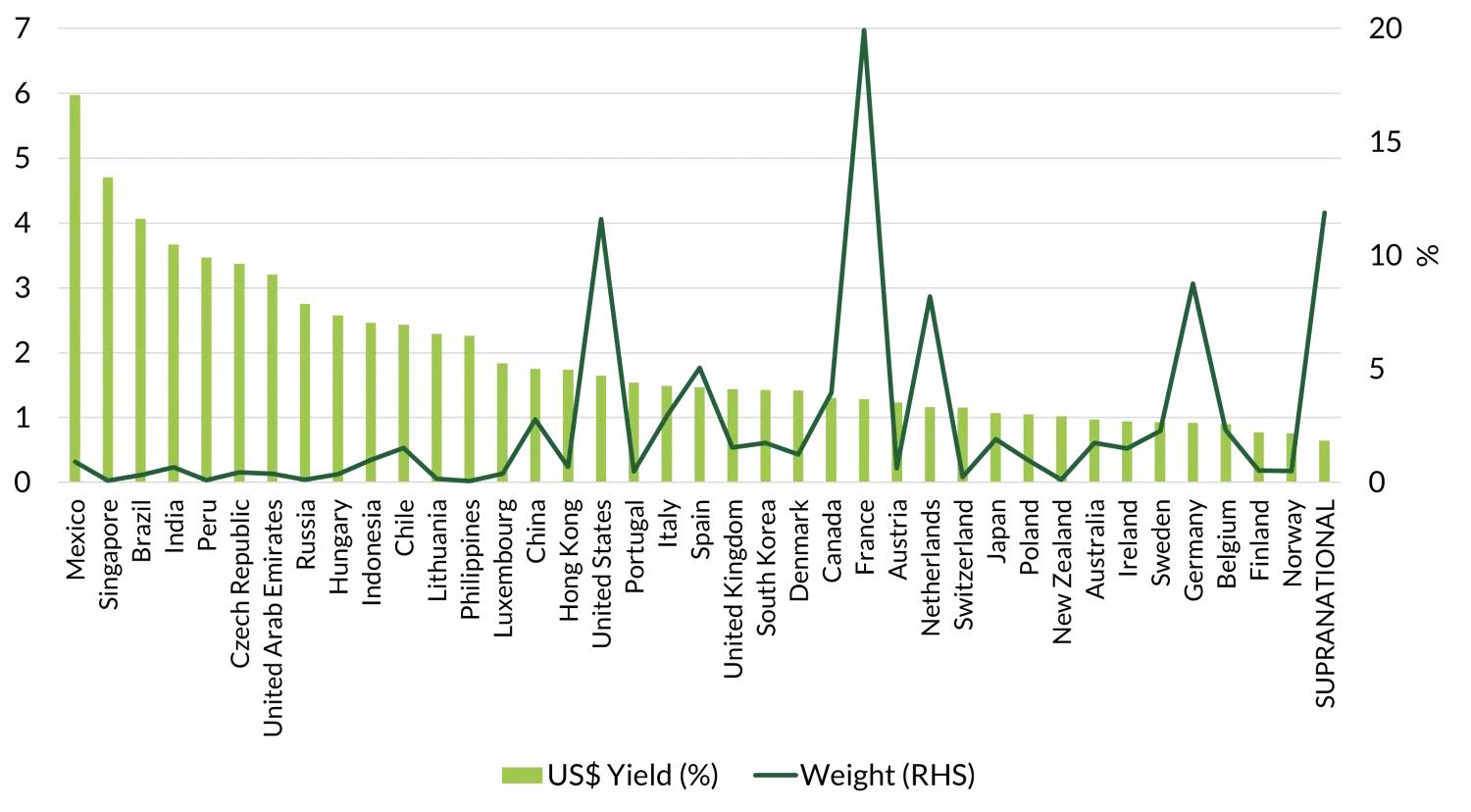

By broad sector, just over half of all green bonds are corporate issuers at 52%, while sovereign linked issuers comprise 48%, and we think this has important implications for the yield, return and volatility profile of this benchmark as well, as we shall see later.

Looking in more detail, Utilities are the single biggest sector, with Banks a surprising second given the relative tiny weighting of Energy companies which most would expect to complement Utilities given their natural overlap.

Chart 5 – Sector weights:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020.

The large composition of sovereign-linked, and beyond that, traditionally high cash flow sectors, can lead to a significant lack of yield from the asset class. Other than in the early days, with few bonds and little diversification, in recent years we have seen green bonds trade at a significant premium to other credit, yielding approximately half of global IG credit as shown below (all yields below shown in USD terms).

Chart 6 – Green Bonds Yield (%) vs Other Fixed Income:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

As you can see from the above chart, green bonds today yield even less than the US Broad IG index, which is of course dominated by US Treasuries, showing that the yield on this index is surprisingly low, no doubt one of the major attractions to issuers within this space. Given the average duration of the benchmark is also high, at around 8 years, it is not the case that yields are low because the average maturity is also low – quite the reverse in fact.

Looking within the broad ratings bands, the credit split is remarkably diverse with each band comprising at least 20% of the index. However, this masks the quite significant yield and duration differentials within each ratings band, and the relationship between yield and duration therefore is stretched when compared to broader fixed income, as shown in Chart 7 below. For reference, the global fixed income universe of sovereign and corporate fixed rate bonds has an average duration-to-yield ratio of less than 5, whereas green bonds have an average duration of 6.86x their yield at the index level, which exceeds 12 for the AAA and AA components, however.

Chart 7 – Yield and Duration Ratio by Rating:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

In simple terms, the higher quality half of the index has yields so low, and durations so high, that a rise of 1% in those yields would see capital losses that equate to the income from 12 years of coupons. Alternatively, a rise of just 10bp in yield would see losses exceed a year’s worth of income.

But when you dig a little deeper, however, it is possible to find some yield in green bonds. Extracting this yield however does likely mean exposing investors to small parts of the index, often from countries with a mixed record on human rights and other ESG metrics, and the special purpose vehicle (SPV) nature of many of these bonds in our view requires very detailed and time consuming due diligence to be applied before any of these investments could ever be deemed acceptable.

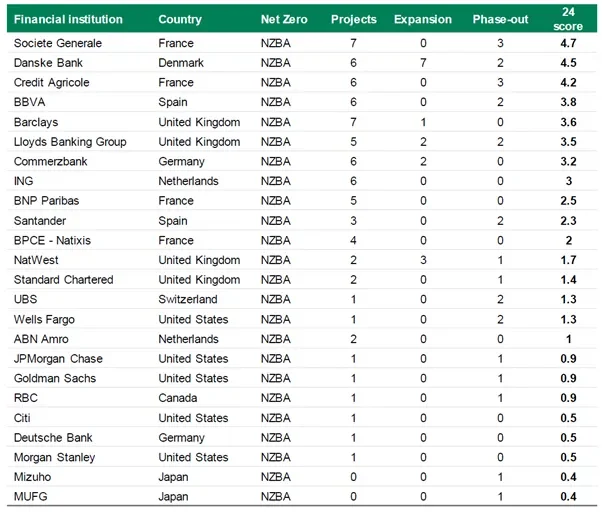

As Chart 8 shows, large parts of the index yield little; instead global IG investors must venture ‘off-piste’ into Mexico, Brazil, India, Peru, the UAE and Russia in search of yield.

Chart 8 – Green Bond Yield by Country:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

So, given these characteristics, what has the investor experience been in the asset class?

Since inception, green bonds have delivered less than half the annualised return of other IG credit, and less than half the return of broad IG fixed income including sovereigns.

At the same time, volatility of the asset class has been more than double the US broad IG universe, and 1.6x the volatility of global IG credit.

As shown in Chart 9 below, the investor experience has been the poorest in terms of risk-adjusted return, achieving a Sharpe Ratio of just 0.23 vs. 0.84 for Global IG credit, or above 1 for US Broad IG.

Chart 9 – Returns and risk-adjusted returns of Green Bonds vs Other Fixed Income:

Source: TwentyFour, ICE/BAML, as at June 30, 2020. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. It is not possible to invest directly into an index and they will be unmanaged.

While drawdowns in March 2020 were less than IG corps, they were not significantly better than US Broad IG, so it seems the downside risk is not materially better either.

While individual green bonds may well have specific characteristics that make them good investments, it is clear to us that, historically at least, the asset class overall has struggled to compete with other risk assets. With less than half the yield, less than half the return, and double the volatility, if these trends do continue, the asset class does not seem attractive from a pure risk-reward perspective relative to other areas within fixed income.

Examples of three contrasting green bonds

Before concluding our paper we thought that the reader could garner even more information by looking at three examples of ‘green’ bonds. One that we view as a successful example, one not so and an issuer who has moved away from issuing green bonds in favour of linking its debt to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

SSE green bonds

Our first example is utilities company SSE plc, a FTSE 100 energy company with operations and investments across the UK and Ireland. It is involved in the generation, transmission, distribution and supply of electricity, the production, storage, distribution and supply of gas and in the provision of energy-related services. Naturally as a utility company SSE was in a position to influence change and transition to a lower carbon electricity system. Since 2010 SSE has been investing in renewable energy (over £3.9bn to date) and has the largest renewable energy capacity in the UK and Ireland. This focus accelerated in 2015 when the company produced its first Sustainability Report. The report detailed social, environmental and economic impacts with Key Performance Indicators for each part of their business, including a sustainability overview section, while outlining SSE’s future plans. SSE increased their frequency to a bi-annual Sustainability Report in 2016 and aligned their objectives to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2017 SSE announced its first green bond (€600m 0.875% Coupon, +38bp vs mid-swaps) as they believed it demonstrated their long-term commitment to the principles of sustainability and the transition to a low carbon economy. For the issuance SSE produced a Green Bond Framework which sets out SSE’s Green Bond Principles and its use of proceeds, which is summarised at the website below:

SSE Green Bond Framework:

“SSE intends to use the proceeds from the issuance of the Bonds to finance or refinance SSE’s £1.1bn Eligible Green Projects. The SSE Green Bond Framework defines Eligible Green Projects as projects that fall into the following categories:

– Renewable Energy Production: Windfarm (Onshore Windfarms and Offshore Equity Investments).

– Renewable Energy Transmission: Onshore Transmission Network Infrastructure.

DNV GL Business Assurance Services Limited has been commissioned by SSE to provide a Green Bond eligibility assessment on the Bond.”

DNV GL’s 2017 Green Bond Opinion on SSE’s Green Bond Framework:

SSE committed to update investors each year on the allocation of proceeds and environmental impact from the bond. SSE’s Green Bond Framework and DNV GL’s Annual Green Bond Opinion reports are detailed on the SSE website, along with PwC LLP’s independent assurance of allocation to specific eligible green projects. SSE has followed up its inaugural €600m green bond in September 2017 with a second €650m transaction in September 2018 and a third £350m deal (issued out of Scottish Hydro Electric transmission which is a subsidiary of SSE) in September 2019, making SSE the largest issuer of green bonds in the UK corporate sector.

There is clear evidence to us that SSE’s green bonds have had, and are continuing to have, their desired effect outlined by SSE to commit to sustainability and the transition to a low carbon economy. In 2013 SSE’s coal usage was 20 TWh (Terawatt hours), or 59% of its production input, and after facing multiple pressures to reduce its coal dependency, the firm made a commitment to substantially reduce this number over time. By 2019 coal usage had fallen to 0.9 TWh, less than 5% of input, by substituting with gas, hydro and wind. SSE closed its last remaining coal plant in March 2020 – the original target was to be ‘net zero’ coal by 2025.

Chart 10 – SSE electricity generation from coal:

Please note SSE’s figure for 2020 has not been released at the time of writing. Source: TwentyFour, Bloomberg, SSE, as at July 27, 2020.

SSE has added to its sustainability targets and by 2030 aims to treble its renewable energy output to contribute 30TWh a year, cut its carbon intensity by 60% (120g CO2/kWH target) and build the flexible electricity network and charging infrastructure to help accommodate up to 10m electric vehicles across Great Britain. SSE’s current and future green bonds will directly contribute towards these targets as a consequence of their focus on renewable energy production and transmission.

We believe the approach SSE has taken, with a detailed and transparent framework, separate assessment and audited process, is a good example of how green bonds can work both outright and help to move the company as a whole towards their environmental goals; achieving the outcomes typically desired by investors and helping to produce a sustainable future for all.

Repsol green bonds

In May 2017 the Spanish energy major Repsol issued the inaugural green bond from the Oil and Gas sector. The five-year, €500m bullet bond was welcomed by the market and unsurprisingly attracted widespread attention from both the media and investors.The use of proceeds is the most important part of any green bond and is noted below:

“The Green Bond will allocate €500 million to investment projects aimed to avoid GHG emissions by around 1.2 millions of tons of CO2eq. This includes the refinancing of implemented projects since 2014, and financing of two Eligible Projects categories solely in our production facilities: (i) Energy efficiency projects and (ii) Low emissions technologies.”

Vigeo Eiris was used to provide an independent Second Party Opinion on the “sustainability credentials and management” of the bond, which it passed citing “positive contribution to sustainable development, aligned with the Green Bond Principles”.

On the face of it this bond ticked all the green boxes; very transparent, externally reviewed, meeting all four Green Bond Principles and appearing to help Repsol transition from ‘brown’ to ‘green’. However, looking more closely at the breakdown of the use of proceeds (details available here) this transaction actually upgraded and optimised current equipment at their chemical and refining facilities in Spain and Portugal. The claim that the bond would facilitate the reduction in carbon emissions by 1.2m tonnes annually should also be put in context as Repsol’s 2016 emissions were 19.7m tonnes (excluding emissions from consumption).

Thus, thinking about actual outcomes further, this apparent ‘green’ bond simply upgrades fossil fuel burning assets, extending their lifespan, improving efficiency, increasing company profitability and in absolute terms increases total emissions over the life of these assets. A potential win for shareholders, but not the environment.

As you would expect this bond attracted much controversy and it was subsequently excluded from many green bond indices, but this didn’t stop investor demand. The deal was announced to the market with initial price talk of mid-swaps +55bp, subsequently revised to +40bp following a €2.7bn order book and then tightened further to +35bp at launch, with the coupon set at 0.5%. What is particularly interesting to us is that approximately 45% of the issue was allocated to investors with ESG mandates despite the ambiguity surrounding the green nature of this issuance. Did investors even look at this bond in detail or was a substantial amount of this demand from passive ESG funds?

This bond is funding exactly what we believe the low cost of capital of green bonds should be used to phase out. In our view, this green bond is not aimed at aggressively shifting from a ‘brown’ business model, but rather making it ‘less bad’ in the short term; as we said, a potential win for shareholders, but sadly not the environment. Even if green bonds were always about the asset not the company, then here the asset (a refinery) and subsequent environmental impact in our opinion does not justify a green label.

Enel green bonds

The Italian energy giant Enel was previously one of the largest issuers of conventional corporate green bonds, having raised €3.5bn worth from 2017 to September 2019. These were linked to eligible ring-fenced projects and assets which in Enel’s case were mostly renewables. The company’s high profile green bond programme was very well regarded by pure green bond investors and the wider market. So, in September 2019 when Enel announced it would end its green bond programme in favour of one linked to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at a time when the green bond market was gaining serious momentum, there was much bemusement within the ESG investing community.

So how does an SDG bond work and is this an alternative future model?

The main difference between a green bond and a SDG linked bond is that rather than focusing on a single ‘green’ asset or project, an SDG bond looks at how the firm-wide corporate strategy is aligned with the 17 UN SDGs.

These bonds are linked to one or more of the SDGs and are structured to include covenants which link the coupon of the bond to the issuer’s achievement of these specific SDGs. In principle these bonds create a direct relationship between an issuer’s sustainability strategy and its funding strategy; corporations are economically incentivised to deliver. Taking Enel’s first SDG bond, a 5yr $ benchmark linked directly to SDG 7 which states, “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”. Unlike green bonds, a detailed breakdown of the use of proceeds is not required – all proceeds are simply for general corporate purposes. Enel’s SDG 7 KPI (Key Performance Indicator) states that by December 31, 2021 at least 55% of installed capacity will be from renewable sources; if this target is missed there will be a one-time coupon step-up of 25bp (at the time of issuance renewables made up 48% of installed capacity).

Despite the controversy surrounding this new bond format there was clear investor appetite, with $4bn of orders. This demand drove pricing to around 20bp inside Enel’s existing curve. Bankers on the deal said feedback was excellent, with about 70% of allocations going to ESG mandates.

The SDG bond market is very young and there are many unknowns for investors and issuers. What we do like about SDG bonds is the firm-wide link to long term sustainable outcomes. Many investors argue that by loosening the rules, SDG bonds will open sustainable and cheaper funding opportunities for issuers – often SMEs – that so far have been unable to issue green, social or sustainability bonds because they cannot identify sufficient eligible assets or projects. Coupon step-ups go further in incentivising a positive outcome, thus helping to align the interests of issuer and investor.

Clearly we need to see how and if this market develops and analysis has to be carried out on how easy the targets were to achieve. Would they have been achieved anyway? Is the audit process robust? If use of proceeds is less defined, will leakage continue to be an issue? What if the company is failing on other ESG or SDG areas?

Yet again we cannot escape the fact that analysis is required over box-ticking if we want to try to ensure credibility and desirable outcomes.

Conclusion

The green bond research presented here did not start out as a whitepaper, but rather an attempt to answer the question posed in our introduction, ‘Do Green Bonds Work for Investors’ and if so ‘should we launch a green bond fund’? Along the way we learned some new information and found some common ESG themes that we have commented on in the past. We care about improving environmental and other ESG outcomes at TwentyFour, and so on the face of it, green bonds should be a market segment that we look to embrace fully and therefore potentially launch a fund to help investors access this market. However, there are a number of areas where we just cannot currently get comfortable, mainly that such a fund does not make sense on a risk-adjusted return basis and possibly not even on an expected environmental outcome basis. That is not to say that there are no green bonds worth investing in: we have invested in green bonds and would expect to continue to do so when deemed appropriate.

The news is not all bad, though. Clearly investors have a significant appetite for funds and bonds that are ESG friendly, sustainable or ‘green’. Indeed, the European Council has proposed that 30% of its €750bn Recovery Plan should be targeted toward green bonds. As we write this paper we have seen the first green AT1, Tier 2 and hybrid issues. We think companies need to be more positive and constructive to tap into this demand and capital markets along with regulators need to progress standards and transparency. We need to be careful however of cheaply funding ‘green’ parts of a business while ignoring what goes on, from an ESG perspective, in the rest of the company. We would urge investors to do their own proper due diligence on this rapidly growing asset class, but clearly there are many question marks raised in this paper.

The main recurring theme is that we firmly believe to be truly effective in this field you have to actively do the analysis and think about the outcomes. We are active managers and as we blogged about on 1 June 2020, when you start to add ESG/Sustainable or green bonds into the mix, in our view tick-box passive funds come up short and will slow real progress.

Right now we feel that selectively buying green bonds that make sense for our mandates, whether designed specifically with a focus on ESG/Sustainability or not, is the best way we can go about looking after our clients’ interests because our ESG integration model in particular does what green bonds are supposed to do anyway.

Moreover the research contained in our whitepaper, ‘Sustainable credit: A free lunch? ’ suggests that returns are potentially not compromised either.