Sustainability and ABS – what’s going on?

Since we published our October 2019 whitepaper, ‘ESG and ABS at TwentyFour’, the global ESG market has continued to grow dramatically.

ESG bond funds accounted for 10.8% of all bond funds globally in August 2022, up from 7.1% at the end of 2020, though the trend is more developed in Europe than it is in the US; ESG funds account for 22% of European bond funds’ asset under management, versus only 1.5% for US bond funds1.

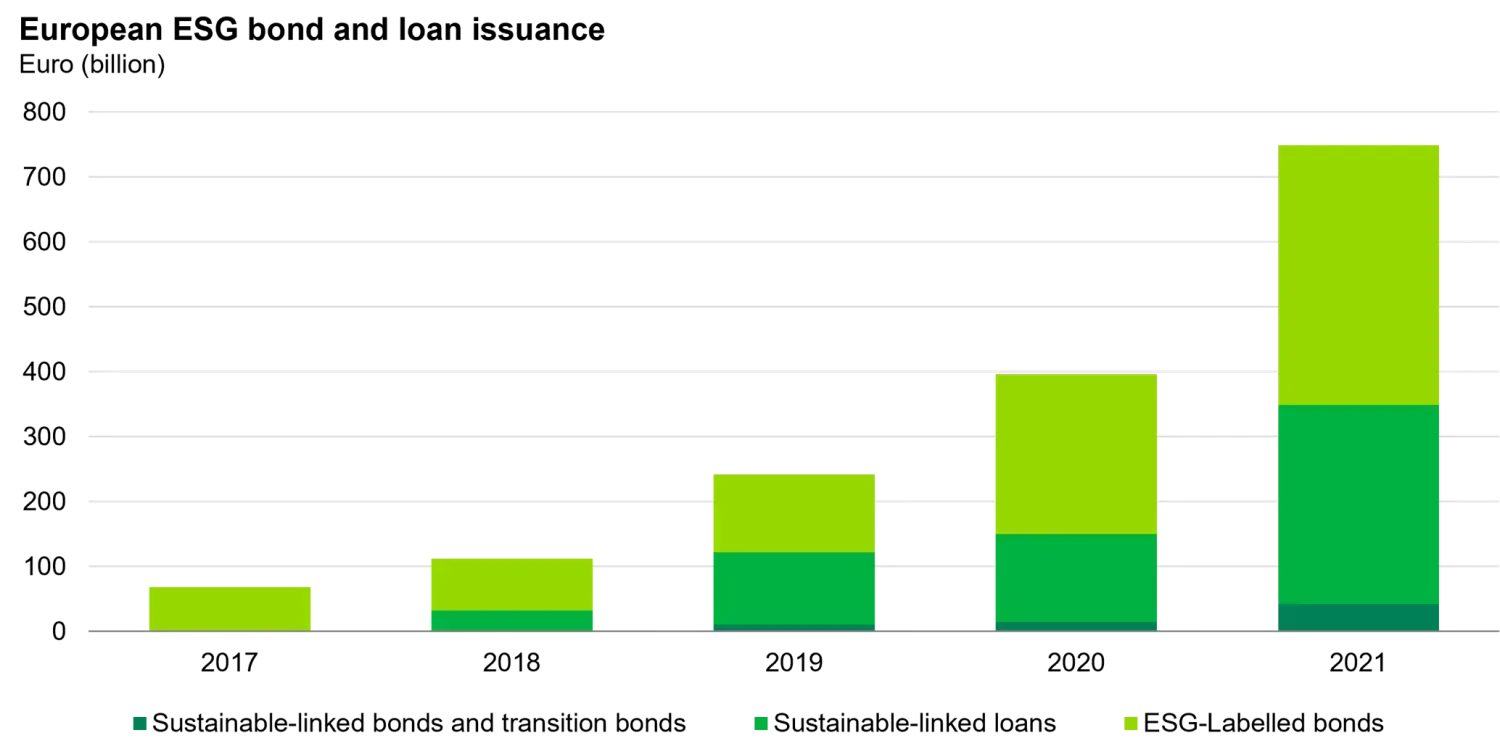

Sustainable issuance in fixed income has also continued to grow rapidly, with ESG bond and loan issuance in Europe in 2021 totalling €749.8bn, almost double the 2020 figure2.

Source: AFME, 23 February 2022

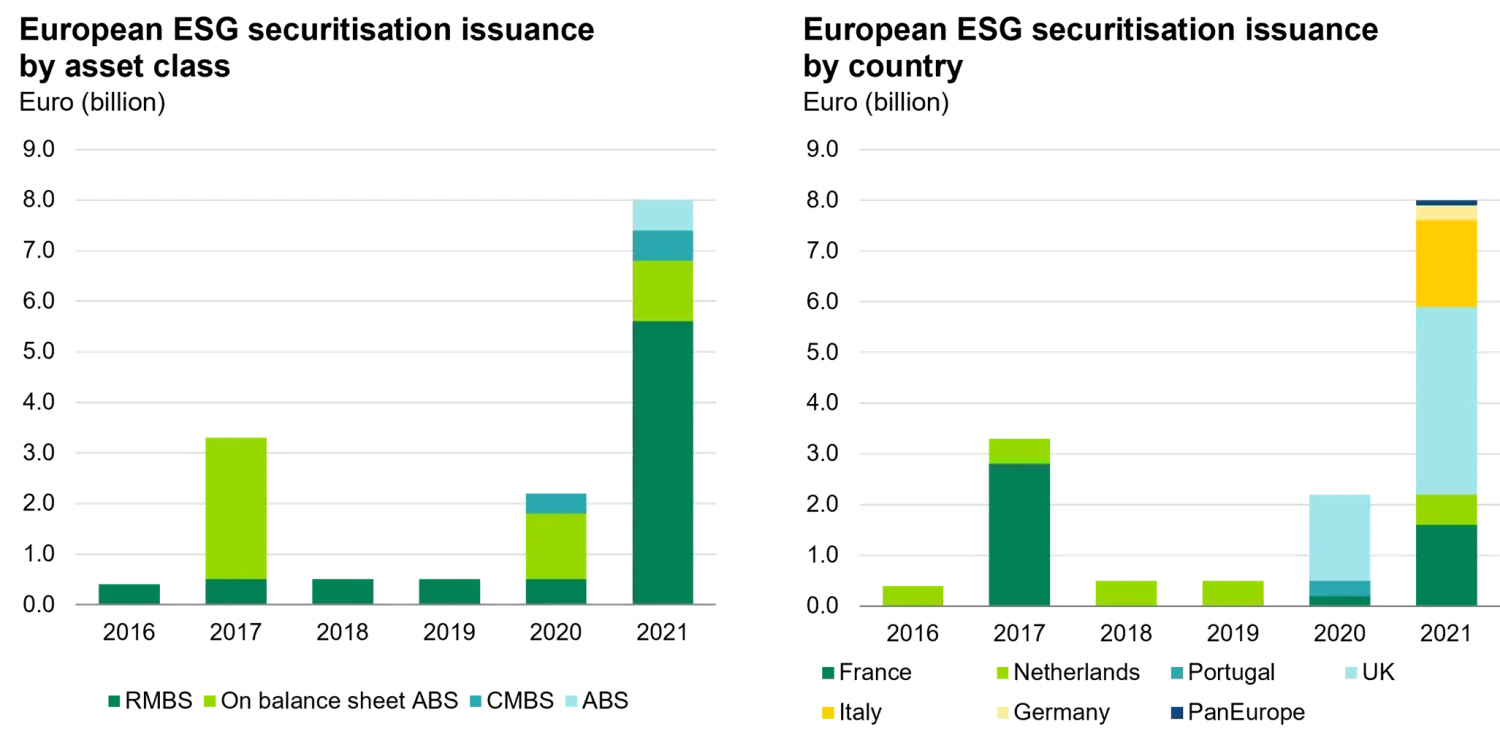

Despite this strong growth, the share of ESG bond issuance in European ABS has been very low, notably lagging issuance in the covered bond market. In fact, ESG transactions accounted for just 8% of total European ABS issuance in 20213. While Dutch Green RMBS transactions have been issued consistently over the past few years, the diversity of ESG securitisations improved markedly in 2021, encompassing RMBS, ABS and CMBS trades from more jurisdictions including the UK, France and Italy.

Source: AFME, 23 February 2022

In fact, up until a couple of years ago ESG or sustainable securitisation was yet to be defined. Regulation governing Green or Social ABS, for example, hadn’t been established, partly due to several challenges presented by the unique features of the asset class. Namely, these would include a lack of third-party data providers (some examples prominent in other markets are MSCI, Asset4 and Sustainalytics) actually scoring ABS transactions, the consequent lack of comparable benchmarks, and the limited disclosure of specific ESG data applicable to ABS. These limitations have been driven largely by the more complex structure of ABS deals when compared to typical corporate or government bonds, as well as the fact that unlike corporate bonds, ABS assets sit in a special purpose vehicle and the structures have thus been slower to adapt to companies’ rapidly changing sustainability strategies.

With securitisation there are simply more elements to be considered when analysing the sustainability of a transaction, such as the nature of the assets, the structure of the deal itself, and the multiple parties attached to the issuance – lender, sponsor, servicer.

However, in the last couple of years investors, industry bodies and regulators have joined forces to move towards establishing a level playing field across all capital markets instruments by improving ESG disclosures, and by setting guidelines for assessing ESG factors in securitisations. Being able to contribute to a more sustainable economy, whether on the environmental or social side, is crucial for us as bondholders, and below we highlight some of the latest developments and achievements made in sustainable ABS.

The principles of Green ABS

Firstly, we have seen a Green ABS market begin to emerge. This should represent an important pillar of ESG and sustainable bond issuance in ABS, though it is only part of the puzzle in our view.

In September 2020 we published a whitepaper, ‘Do Green Bonds Deliver For Fixed Income Investors?’, which focused on the corporate and sovereign sectors. Our general conclusion was rather negative at the time, because we felt the value proposition did not stack up for investors. The reason for this lack of value was beyond the scope of that whitepaper, but we believe it was driven by an imbalance of demand and supply as the asset class raced into being.

Essentially, green bonds were a victim of their own success; overwhelming demand driving yields lower meant investors could expect poor risk-adjusted returns, and just as importantly there was little pressure on bond issuers to tighten up their deal structures, hence the unease we had over the use of proceeds from these early green bonds. This was in sharp contrast to the birth of bank Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds, for example, where healthy investor scepticism produced a more constructive and traditional development process for a new product. The first AT1 bonds had to justify their place in investors’ portfolios, and they did this in two main ways. First, attractive pricing encouraged investors to make the effort to analyse the structure and the risks. Second, issuers had to work hard with investors to fine tune the structure, such that the iterative process of establishing an acceptable structure was largely complete in a relatively short period of time.

With the emergence of Green ABS, issuers, regulators and investors have the experience of these other asset classes to draw on as they look to build initial credibility and market acceptance.

For example, to help address the structural problems of green bonds in general the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) produced a set of issuance guidelines in June 2021 called the Green Bond Principles (GBPs). The main focus of the GBPs is transparency, with an emphasis on use of proceeds, management of proceeds, and project evaluation and selection. The GBPs remain voluntary, but such efforts should help to address some of the structural concerns our 2020 whitepaper highlighted.

However, no guidelines for securitised bonds were included, and the GBPs criteria weren’t particularly helpful for Green ABS. Given ABS bonds are backed by a defined pool of assets and don’t finance part of the issuer’s business, there was a previous inclination to only consider transactions backed 100% by ESG collateral as Green ABS. This slowed down early green issuance as only lenders originating enough green assets could issue Green ABS.

The European Supervisory Authorities, or ESAs (the EBA, EIOPA and ESMA), addressed this specific point, among others, in a 2021 report about the development of a sustainable securitisation framework. This recommended to apply the use of proceeds methodology at the originator rather than issuer level, to allow transactions not backed 100% by green assets to be eligible under the GBPs. This is an important concept as it recognises the lack of green assets to securitise, and proposes a pragmatic approach to allow lenders to finance the transition by committing the proceeds of the bonds to finance green assets.

The ESAs’ proposal was integrated into the GBPs by ICMA in June 2022, which means there are now two types of securitisation that qualify:

- A ‘secured green collateral bond’ would apply to an ABS deal backed by 100% green collateral, such as residential properties with an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of A or B, electric vehicles, or commercial properties with ‘very good’ BREEAM4 ratings.

- A ‘secured green standard bond’ would apply to an ABS deal whose proceeds can be applied outside the securitisation, and can be related either to assets included in the portfolio or new origination not included in the pool. This label can also be applied to a single tranche of a larger ABS deal, with the proceeds used to finance green projects of the issuer, the originator or the sponsor.

Dutch lender Obvion’s Green Storm RMBS, issued in 2021 and backed by energy efficient properties rated A in the Netherlands, adhered to this framework, as did UK specialist mortgage lender Kensington Mortgages’ Green Finsbury Square RMBS. Kensington directs proceeds from the Class A notes of that deal to eligible green projects, such as UK owner-occupied or buy-to-let home loans secured on properties with a minimum EPC rating of B, which currently signifies an emissions intensity in the lowest 15% of residential buildings in England and Wales. In this case, Kensington has five years to allocate the proceeds to green projects and reports annually on the management of its proceeds.

Slower emergence of Social ABS

When it comes to Social ABS, we believe there are questions that remain to be addressed, such as whether investors should look at social factors at the originator level or the servicer level, and whether investors need to assess the social aspects of the assets backing a transaction. Hence it is no surprise green deals have been more popular than social ones so far.

Similar to the GBPs mentioned above, ICMA has provided guidelines around these issues by developing a social bond framework. Under the Social Bond Principles (SBPs), social bonds are described as ‘use of proceeds’ bonds that raise funds for new and existing projects with positive social outcomes, preferably for target populations. Social projects as defined by ICMA include, for example, access to financial services and affordable housing (such as the Help To Buy and Right To Buy schemes in the UK). Examples of target populations include underserved, excluded or marginalised groups, ageing populations and vulnerable youth.

In June 2022, ICMA added the use of proceeds methodology to its framework, in line with its addition to the GBPs, to include both ‘secured social collateral bonds’ and ‘secured social standard bonds’ as eligible Social ABS.

In terms of Social ABS issuance, we have recently seen transactions backed by various types of collateral (credit card receivables, mortgages and auto loans being the most common), with the proceeds earmarked for projects or assets with positive social benefits. Gemgarto 2021-1, a UK RMBS again issued by Kensington Mortgages, provided owner-occupied mortgages to borrowers with more complex incomes that are typically underserved by high street lenders, such as self-employed borrowers, first-time buyers with a limited credit history, contractors, and retired or younger borrowers. In Brass No. 10, a UK Prime RMBS from Yorkshire Building Society, the proceeds will fund higher rate savings products, as well as improving access to competitively priced mortgages for first-time buyers and underserved borrowers with complex incomes.

Despite ICMA’s efforts to establish guidelines, this framework does not provide a definition or criteria for social securitisation specifically, and thus we believe investors need to scrutinise Social labelled ABS transactions individually to assess whether social benefits like access to finance are achieved or not. Charging unaffordable interest rates on a product for underserved borrowers, for example, would create the opposite effect.

One example of a questionable deal in our view was Fortuna 2022-1, an ABS issued by German digital consumer lender AuxMoney in May 2022 that carried a social label on the senior notes, which were fully backed by assets derived from a financial inclusion project. In fact, 77% of the portfolio’s loans were made to borrowers underserved by traditional lenders due to a low credit bureau score (E or lower), or borrowers underserved due to demographics (under 25 years old or over 65). However, on closer inspection (via the investor presentation) the pool had an average interest rate of 9.9% for 5-7 year fixed rate consumer loans, with some borrowers charged as much as 17%, in order to compensate the lender for the expected high default rate. The annual default rate has been running at over 7%, which in a relatively benign environment with low unemployment suggests to us that borrowers are struggling to keep up with unaffordable rates. The social label of the senior Class A notes appears questionable here in our opinion, and we would call this sub-prime lending rather than responsible lending.

On this topic, the UN’s Principles of Responsible Investment organisation recently ran a workshop bringing together banks, lenders and investors to discuss social lending initiatives, social securitisations and the challenges of social data collection.

Sustainable data improving

What these frameworks have brought to the surface is the need for more comprehensive ESG data disclosure in ABS, regardless of a deal being labelled as social or green. One thing that the ESG and sustainability movement has highlighted is that if we cannot measure, then we are in the dark as to the progress being made.

In 2021, the EU took a further step by amending its Securitisation Regulation and introduced, among other things, new optional disclosure provisions for Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) securitisations related to the principal adverse impacts (PAIs), which are a set of indicators describing the sustainability characteristics of the underlying assets. In response, the ESAs published draft Regulatory Technical Standards setting out recommended factors and methodologies for market participants in assessing potential negative ESG impacts, which has helped to clarify some of the challenges investors face when analysing securitised assets.

Investors are indeed increasingly requesting ESG information on the sponsor or originator of ABS transactions, as well as on the underlying collateral itself. To address this, the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) launched an ESG questionnaire which has now become a standard part of the marketing material for ABS transactions, available to all investors. The questionnaire provides ESG disclosures on the originator and servicer of the assets, as well as data on the assets themselves. TwentyFour was a part of the AFME working group that developed this questionnaire and we believe it takes ESG data disclosure in ABS to a much better level, and as such we expect to see rapid uptake of its use in the market for new issues.

As a result, lenders are now able to provide energy efficiency data (property EPC ratings) on a pool of mortgages, and are also in the process of calculating their Scope 3 emissions. As bondholders, this means we can assess clearly what we are financing, and we are better able to engage and push lenders to offer borrowers all the tools available to improve the carbon footprint of their homes. Consequently lenders are better incentivised to contribute to net zero emissions targets over the coming decades, by launching green mortgage products and retrofitting options to borrowers. Green products include lower interest rate deals for properties with an EPC rating of A and B, and ‘cashback’ products where the borrower is incentivised to improve their current EPC rating.

Green shoots for ESG CLOs?

There has also been an increasing focus on ESG in the leveraged loan and CLO markets.

Sustainability-linked issuance in the European leveraged loan market is a relatively new phenomenon, having only begun to emerge in 2021. Leveraged loans – loans to typically lower rated private companies – are the main underlying assets of CLOs, and due to the private nature of these companies ESG data transparency has historically been extremely limited. The European Leveraged Finance Association (ELFA) has worked with its US counterpart to significantly improve transparency and disclosure in leveraged loans, creating standardised ESG factsheets for each sub-industry that have been added as supporting documentation for new loan transactions.

ELFA has also launched a new initiative bringing together CLO investors and CLO managers, so that managers can better understand investor requirements on ESG data reporting, and investors can better understand what data managers can practically get on their loan pools. A large number of CLO managers are members of ELFA, covering around 70% of European CLO deals, which should give the initiative meaningful influence.

Over the past nine months one ELFA working group has focused on ESG disclosures for CLO managers themselves, and created a standard questionnaire for managers consisting of two parts: one to provide information on their sustainability strategy at the corporate level, and another one to provide detail around their own ESG investment policies; TwentyFour contributed to the development of this questionnaire, which was published by ELFA in October5. The aim is for the CLO questionnaire to become the market standard, and a part of the typical marketing material for new CLOs where it will certainly improve transparency and data disclosure in our view. For investors we believe it will allow better comparability across CLO managers once it is widely adopted.

Another ELFA working group is focused on data disclosures within CLO transactions, specifically ESG data from the underlying credits, such as carbon emissions figures, diversity and gender pay gap data, revenues from ‘sin’ sectors, compliance with policies and so on. In 2021 and 2022 we saw the issuance of CLOs applying not just a negative screening approach, but also increasingly a positive tilt towards better companies from an ESG perspective. Data reporting has improved substantially in recent years, and we believe the ELFA industry initiative will help enhance transparency even further, with some CLO managers for example already working on carbon emissions reporting and PAI disclosures.

In other developments in this space, September 2022 saw ratings agency Fitch launch an ESG rating methodology for leveraged finance, and it has been working to score the European leveraged loan market, to provide a standardised approach to ESG scoring and to improve comparability across CLO managers. This could ultimately lay the ground for the issuance of ESG CLOs, but more immediately we think would offer investors more transparency on the ESG characteristics of the underlying loans, since investors have so far been relying on individual CLO managers’ own scoring methodologies.

Issuer-investor engagement is key to further progress

What does all this mean for investors?

First, investing in such bonds could contribute towards voluntary and regulatory sustainability mandates, and slowly close the gap between securitisation and other capital markets instruments.

Second, lenders will be better incentivised to further boost green and social issuance volumes knowing they will be backed by greater support from investors.

Sustainable and ESG securitisation is an exciting development for the ABS industry, and at TwentyFour we are pleased to have contributed to achieving new standards through constant engagement with originators, arrangers and other investors.

There remains more to do, particularly in encouraging the adoption of these initiatives, but from a low base we are encouraged to see the ABS market responding to the ESG and sustainability challenge. In other words, a win-win outcome for the markets and the planet.

_________________________

1 BofA Global Research, 4 October 2022

2 AFME, 23 February 2022

3 AFME, 23 February 2022

4 Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method

5 https://elfainvestors.com/publication/clo-esg-questionnaire/